There can be a disconnect between everyday life and the natural world, but a healthy diverse environment, where humanity can thrive, requires collective action to address the threats from climate change and development.

A healthy environment is productive and best for sustaining human well-being, but many of us live in the built world and are disconnected from nature. This disconnect can make it difficult to conceptualize the changes that are reported as they are not within our individual experience. Quantifying anthropogenic environmental change and the associated risks is difficult, but the planetary boundaries framework does this through the definition of nine Earth system boundaries — climate change, biosphere integrity, land-system change, freshwater use, biogeochemical flows, ocean acidification, atmospheric aerosol loading, stratospheric ozone depletion and novel entities — that are needed for a stable and resilient planet and aims to define safe limits for human impacts. Research has assessed the status of these boundaries, most recently in 2023 when Katherine Richardson and colleagues found that six of the nine boundaries had been transgressed1, including biosphere integrity, in particular the loss of genetic diversity. And a recent study used integrated assessment models to project to 2050 and found that under current policies and trends, the situation will decline for eight of the nine boundaries2. Ozone depletion is the exception, highlighting how policies, such as the Montreal Protocol, can effect change, with the authors highlighting targeted policy interventions to a more sustainable pathway2.

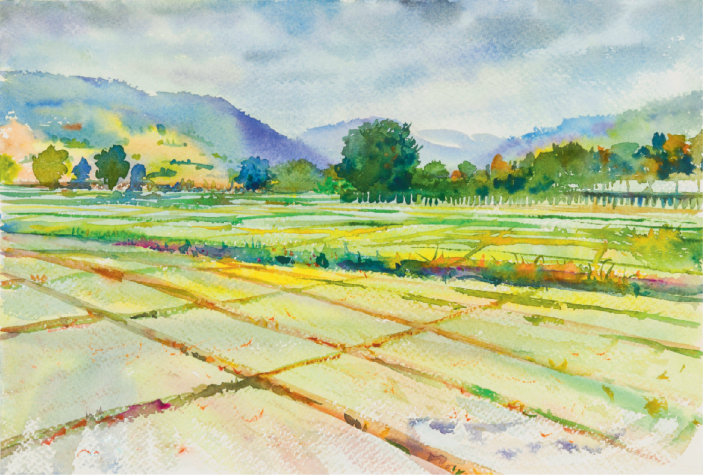

Credit: Tanom Kongchan / Alamy Stock Photo

Any interventions do need to be carefully considered to ensure that they are beneficial without unintended negative side effects. In an Article in this issue of Nature Climate Change, Shelby McClelland and colleagues consider the adoption of natural climate solutions in croplands. Food demand is increasing around the world, making it essential to maximize yields while minimizing the loss of forests and nature to meet this demand, yet the effect of natural climate solutions, such as rotation of cover crops and no tillage, for climate mitigation on yields is unclear. Modelling the emissions and crop yields to 2100 showed different responses that are not always good for climate efforts and yields; the authors highlight the risks to food security and the need for balance when implementing climate actions.

Another recent study considered how climate pledges to meet international climate goals will impact land-use strategies and the implications for croplands and food security, and highlights that the global south will face cropland losses with risks to food security3. All these studies highlight the importance of taking a holistic view when climate action is considered, exactly as the theme for this year’s International Day for Biodiversity, which was on 22 May, advocates — harmony with nature and sustainable development. This needs to be reflected in action by integrating approaches to conservation of the natural world to optimize animal and ecosystem health while ensuring a healthy society, an approach termed One Health.

Climate change and in particular increasing temperatures are already pushing species to shift from their historical ranges, as shown by Laura Gruenburg and colleagues in another Article in this issue. They assessed vertical and horizontal climate velocities for 63 large marine ecosystems, and find that 77% have deepening isotherms, requiring species to shift deeper to maintain their ideal habitat temperature, but this is small in comparison to the horizontal shifts that can require kilometres of relocation.

The reduction and/or shift in suitable habitats as a result of climate change but also historically driven by land-use change threatens ecosystems and will have cascading effects. A study looking at animal data for more than 70,000 species in 35 classes4 identified at least 3,500 species (which is 5.1% of the assessed species) to currently be under threat due to warming temperatures, increased and intensifying storms, hydrological changes such as drought, and other climate change events. The available data cover only a small number of described species (5.5%), and some classes, such as invertebrates, are underrepresented, so the results on the threat from climate change in the study are only the tip of the iceberg. Biodiversity is under threat, and climate action, as well as a focus on developing sustainably, is urgently needed to preserve the natural world as best we can.