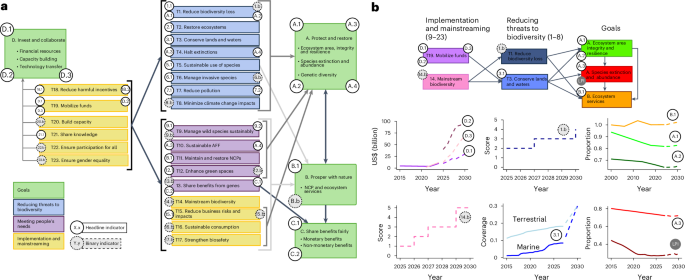

Since the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) was opened for signature in 1992 (ref. 1), three sequential decadal plans have been adopted to address the alarming rate of biodiversity loss worldwide2. The targets for 2010 and 2020 were largely unmet3,4,5. The latest plan, the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), adopted in 2022, is the most ambitious to date6. The GBF hinges on a 2050 vision of living in harmony with nature, to be realized through commitments towards four goals by 2050 and 23 action-oriented targets by 20306. The GBF is built around a theory of change (Fig. 1) that aims to tackle the drivers of biodiversity loss, recognizing that urgent, transformative and widespread action is required across all sectors of society to halt and reverse biodiversity loss.

a, The GBF divides its targets into three categories: reducing threats to biodiversity (targets 1–8); meeting people’s needs (targets 9–13); and implementation and mainstreaming (targets 14–23), which are needed to deliver on its ambition and achieve the four goals. All of them have at least one required indicator (headline, binary or both, shown in circles) to track progress; some of them are related. Implementation of the targets by 2030 contributes to achieving the goals and other linked targets in the GBF. The indicators in the monitoring framework are designed to help track progress along all aspects of the GBF. b, A partial theory of change for some targets (1, 3, 14 and 19) and goals (A and B) of the GBF, with associated indicators, showing how mainstreaming and investment can increase protection and conservation, leading to the goals for species, ecosystems and ecosystem services. Reporting systematically on the required indicators will allow progress to be tracked nationally and globally on each goal and target, enabling action to be taken as needed to deliver on the overall theory of change. Parties may also choose to report on optional indicators (for example, the LPI). Quantitative headline and component indicators can track yearly changes while binary indicators are reported with every national report. Where past data are available, graphs show solid lines. The dashed lines represent optimistic predictions of a world where goals and targets are met. Indicators that are new are shown only with dashed lines because no past data are available to estimate them. AFF, agriculture, forestry and fisheries; LPI, Living Planet Index.

The GBF includes a monitoring framework (Box 1), an important innovation guiding countries on how to report their progress towards the goals and targets (Fig. 1). The monitoring framework sets out how Parties to the Convention are expected to record their efforts and progress using a set of consistent indicators compiled at the national level7,8, while allowing some flexibility because of differing capacity and data availability across Parties9. The monitoring framework was established to improve transparency and accountability among Parties10, recognizing that failure to reach past targets has been linked to low levels of implementation11 and difficulties in tracking progress12. Parties are requested to use the monitoring framework in future national reports to the CBD, including the next (seventh) national report due in February 2026, ahead of the 17th meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP17).

There is now a need for the scientific community and relevant actors to support countries with the design and implementation of their domestic monitoring frameworks, including how monitoring programmes can gather the data needed for indicator updates13. The effectiveness of the GBF’s monitoring framework depends on three key aspects: (1) how well its indicators cover the scope of the GBF’s goals and targets; (2) national uptake of the monitoring framework as a driver for improving national monitoring systems; and (3) the dissemination and sharing of data and metadata on the indicators of the monitoring framework. This Analysis addresses the first of these aspects.

The early process of designing the GBF’s monitoring framework occurred alongside the negotiation of the GBF text and focused on selecting indicators from available lists, such as the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) indicators14 and those generated by members of the Biodiversity Indicators Partnership. This resulted in a list of indicators at several stages of development that was then categorized and matched with relevant goals and targets. The selection process called for at least one headline indicator (Box 1) per goal and target. Where possible, headline indicators were assigned to quantitatively assess progress towards the main intent of the goal or target. Headline indicators were intended to include a small list of indicators to capture the overall scope of a goal or target. This post hoc process resulted in some targets and goals lacking headline indicators. Binary indicators (Box 1) were developed to qualitatively assess progress towards a goal or target (for example, does a legislative framework exist to address the aims of a target?). Where existing indicators were deemed useful for covering a single aspect of a goal or a target, but less relevant for covering its full scope, these were assigned to the optional component or complementary indicator list (Box 1) to allow Parties wishing to report on progress in more detail to do so. Additional indicators that had limited geographical coverage, or which may not be useful or possible to implement for most Parties, were assigned to the optional component or complementary indicator list (Box 1). The list of indicators in the monitoring framework represents a political agreement from Parties on the aspects of GBF that were determined to be the basis for monitoring its implementation.

The scientific guidance for operationalizing the monitoring framework followed the political process of selecting indicators8. Parties established an Ad Hoc Technical Expert Group (AHTEG) on Indicators in April 2023 to provide guidance for operationalizing the monitoring framework ahead of the COP16 meeting in October 2024. This expert group included 45 experts nominated by Parties and observer organizations15 and was tasked with reviewing all the indicators, producing methodological guidance for implementing the monitoring framework, and assessing how well it covers the ambition of the GBF16. The AHTEG included individuals nominated by Parties and observer groups, selected for their expertise on the different aspects of the GBF and representing a diversity of scientific, technical and policy fields as well as Indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLCs) and youth.

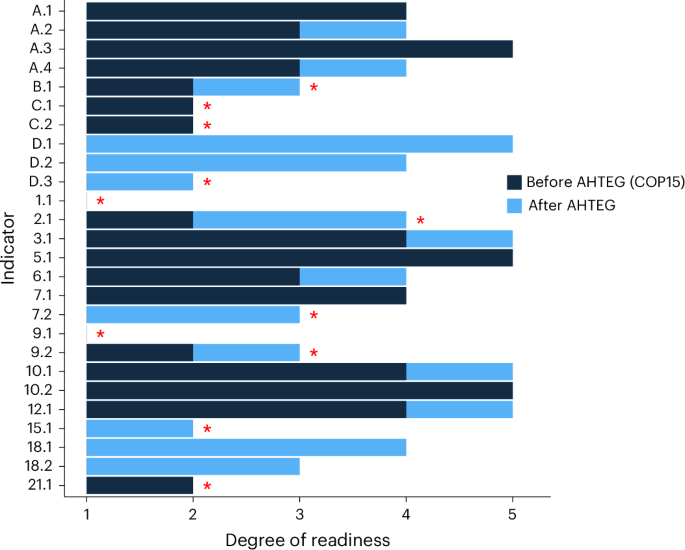

The AHTEG worked with headline indicator developers and agencies supporting methodological research and capacity-building to ensure that each of these indicators had a robust methodology while considering the real capacity constraints, limited data availability and other challenges faced by many parties (Fig. 2). The AHTEG also reviewed all component and complementary indicators to determine the availability of their methodology.

The dark blue bars show the readiness level at the time of COP15 (December 2022), while the light blue bars show the level in June 2024 (that is, reflecting progress since COP15). The red asterisks identify indicators that lacked an agreed methodology when they were adopted at COP15 (ref. 7). Readiness was scored as: (1) methods have not yet been developed and a process needs to be established to develop them; (2) methods have not yet been developed but a process is underway, led by one or more organizations, to develop them; (3) methods have been developed (or partially developed) and tested or piloted, but data are not yet widely available (or collection is not yet underway); (4) methods have been established, data are being compiled and the indicator is operational in at least some countries, but further investment in methods is ongoing or further data collection is required; and (5) methods have been established, data are being compiled and accessible, and the indicator is operational for most or all countries.

The AHTEG conducted a gap analysis, through a multi-step expert elicitation process17,18,19,20 (Methods), to assess the degree to which the current indicators (headline indicators, their recommended disaggregations, and binary, component and complementary indicators; Box 1) cover each of the substantive elements of each goal and target. This gap analysis aimed to highlight limitations in the monitoring framework and support Parties in identifying opportunities to improve its effectiveness and coverage, given that Parties had agreed to keep the monitoring framework under review7. The AHTEG used a consensus-based expert elicitation process to perform the gap analysis. To assess the coverage of the monitoring framework, the text of each goal and target was split into elements (190 in total) reflecting distinct, independently measurable objectives that each need to be achieved for full implementation of the GBF (Methods). For each element, indicators were evaluated and their coverage by each relevant indicator and its disaggregations was assessed (see Box 2 for an example, Supplementary Table 2 for the complete list of elements and Supplementary Table 3 for the detailed assessment). Element coverage was assessed based on the level of development and testing of the indicator and its ability to inform on the element (Methods; see Box 2 for an example). From this, the AHTEG identified gaps and made general recommendations to Parties on improving the monitoring framework in a report for COP16 (ref. 21).

In this Analysis, we—members of the AHTEG and collaborators in the process—(1) present the results of the gap analysis under three implementation scenarios (from worst to best: (i) only required indicators are reported on; (ii) all headline indicator disaggregations are also reported; (iii) all optional indicators are also reported on) and review of the cross-cutting issues of the monitoring framework; (2) share recommendations made to Parties; and (3) suggest the next steps for effectively monitoring the implementation of the GBF. The monitoring framework represents texts negotiated by Parties, so we do not propose revisions to it. Instead, we focus on practical short-term and long-term recommendations for improving biodiversity monitoring that will benefit assessment of progress towards the current GBF and any equivalent future plans.

Gap analysis

Overall coverage

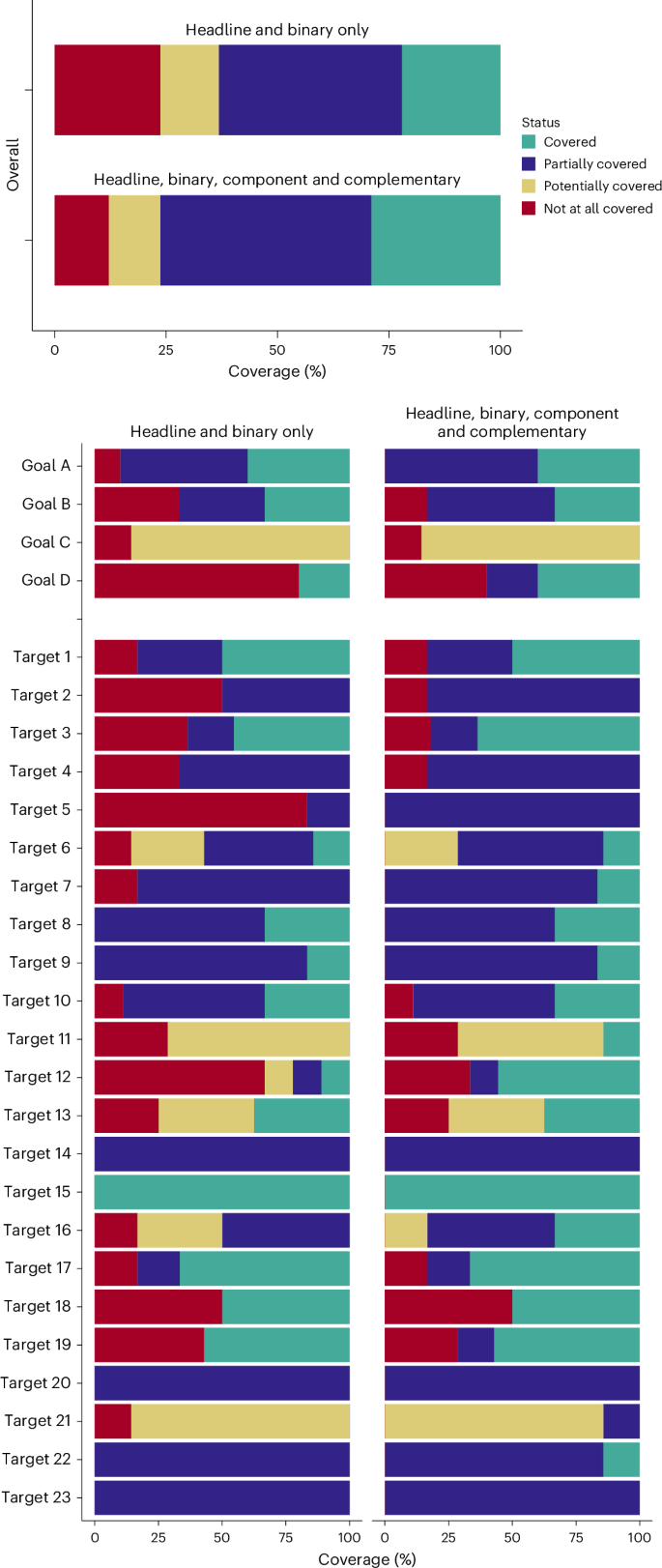

The indicators of the monitoring framework that are required in the national reports (binary and headline indicators without disaggregations) fully cover 19% (36 of 190) of the elements of the goals and targets and partially cover an additional 40% (76 of 190). Applying the recommended disaggregations of headline indicators increases this coverage to 22% (42 of 190) fully and an additional 41% (78 of 190) partially. The use of the indicators that are optional in the national reports (component and complementary) further broadens the coverage of the monitoring framework to 29% (55 of 190) fully and an additional 47% (90 of 190) partially (Fig. 3). Additionally, the use of recommended disaggregations of headline indicators, combined with the optional component and complementary indicators, reduces the number of elements excluded from monitoring of the goals and targets from 29% (56 of 190) to 12% (23 of 190), which implies a reduction of 59% in the number of gaps in the monitoring framework.

Top, overall coverage of the indicators for all goals and targets in the GBF. Bottom left, coverage by the required headline and binary indicators for each goal and target, including the recommended disaggregations of the former. Bottom right, coverage by these indicators and the optional component and complementary indicators for each goal and target. ‘Partially covered’ applies to elements for which the indicator(s) track progress towards some aspects of the element but not all. ‘Potentially covered’ applies to elements that could be covered by indicators that are still in development, so there is uncertainty as to whether the final metric(s) produced will adequately cover the element. ‘Not at all covered’ means that no indicators (headline, binary, component or complementary) are available to monitor the element.

Importantly, many elements are not currently covered (that is, classed as gaps or potentially covered) by the indicators in the monitoring framework: 36–50% for goals (10–14 of 28) and 25–40% for targets (35–64 of 162). Ranges show values with and without inclusion of all disaggregations, component and complementary indicators. If all Parties report only on the required indicators (worst-case scenario), coverage will be limited to the lowest range value; coverage will be even lower if they are unable to report on some required indicators (for example, if data are not available). The highest range value will be reached if all Parties additionally report on all component and complementary indicators (best-case scenario). Realistically, we can expect some coverage in between to be achieved as some Parties choose to report on some optional indicators but not all.

The goals focused on conservation (A) and sustainable use (B) are considerably better covered (90–100% and 67–83% of elements at least partially covered, respectively) than those on benefit sharing (C, 0%) and resourcing (D, 20–60%; Fig. 3). Additionally, there are gaps in the coverage of the monitoring framework for all three sections of the targets: reducing threats to biodiversity (targets 1–8: 28–47 of 54, 52–87% at least partially covered); meeting people’s needs through sustainable use and benefit sharing (targets 9–13: 19–24 of 39, 49–62% at least partially covered); and tools and solutions for implementation and mainstreaming (targets 14–23: 51–56 of 69, 74–81% at least partially covered; Fig. 3).

Headline indicators

Headline indicators alone will only allow partial tracking of progress, completely covering 20 of 190 (11%) and partially covering an additional 29 of 190 (15%) elements, and relating to only 16 of 23 targets. The disaggregations of these indicators, recommended by the AHTEG to enhance their ability to report on elements of the goals and targets, would increase coverage by headline indicators to 26 of 190 elements (14%) completely and an additional 31 of 190 (16%) elements partially.

While in principle the headline indicators can cover elements, in practice, data availability will limit application of many by countries. The coverage of some headline indicators could be improved by expanding geographical or taxonomic coverage through data acquisition and methodological development (for example, A.1, A.3 and A.4). Furthermore, several headline indicators (for example, B.1, 2.1, 3.1 and 6.1) have the potential to cover more elements of their specific goal or target if additional disaggregations can be developed (for example, according to ecosystem type or gender). In some cases, the current lack of potential disaggregations results from a methodological challenge (for example, 12.1); in others, it is due to data availability (for example, 6.1). Improving or broadening data collection for these indicators would potentially improve the coverage of the monitoring framework without the need to develop completely new indicators. Through disaggregation, some indicators may further support management plans targeting specific issues (for example, 3.1 according to areas of importance for biodiversity or by Indigenous and traditional territories; A.1 by drivers or by protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures), in addition to tracking overall progress towards a goal or target.

Some headline indicators have been specifically designed after the adoption of the monitoring framework (for example, B.1, C.1, C.2 and 21.1) and have the potential to cover the respective goals and targets comprehensively but are not yet fully in place. Committing the resources needed to finalize, test and implement their methodologies would enable the monitoring of targets that currently cannot be monitored (Fig. 3).

Some headline indicators are so narrowly focused that they provide very limited coverage of their target; component and complementary indicators are needed to track progress effectively. Specifically, targets 5 and 12 are only sparsely covered because of the narrow focus of headline indicators 5.1 and 12.1 (Fig. 3 and Box 2); both are SDG indicators and cannot be amended easily.

Some targets are likely to require significant effort to fill the gaps identified. Specifically, the headline indicators proposed for targets 1 and 9 remain hypothetical (Fig. 2) and are a high priority for methodological development. In doing so, it may be helpful to identify synergies in data requirements that may simplify indicator compilation. For example, synergies between indicators are possible for targets 5 and 9 (addressing trade in wild species and benefits derived from the use of wild species, respectively).

Binary indicators

The 14 binary indicators cover 13 targets, eight of which have no headline indicator. They will provide a valuable source of information that can be used to rapidly and reasonably assess progress made on taking measures to deliver on goals and targets. However, by their very nature, they cannot inform on the realized implementation (for example, what kind of measures, their breadth or relevance) or outcomes of these measures. As such, they can only track those elements in goals or targets that specifically call for actions (for example, target 15) and not the elements relating to the results of such actions. Therefore, for all targets calling for results and for which only binary indicators are available (targets 8, 14, 16, 20, 22 and 23), only partial coverage of the elements can be achieved with the current monitoring framework (Fig. 3). Efforts are needed to design fit-for-purpose quantitative indicators that can support the binary indicators to cover the outcome elements of those targets. Collaboration may help lower the burden of designing new indicators. For example, Women4Biodiversity developed an indicator on the Gender Plan of Action22 (target 23) and the Global Youth Biodiversity Network is working on an indicator that may be suited to report on targets relevant to children and youth (target 22).

Complete gaps

For 23–56 elements (12–29%, Fig. 2), no indicators are available to track progress. There are three goals (B, C and D) and 11 targets (1, 2, 3, 4, 10, 11, 12, 13, 17, 18 and 19) containing elements that cannot currently be monitored under the monitoring framework (Fig. 3). For some of these (for example, D and 12), the gaps are sufficiently significant that new indicators may need to be added. For others (for example, 3 and 13), extending the methods or identifying disaggregation options for existing headline indicators to cover the gaps might be possible. Other targets (for example, 2 and 4) may require specific indicators to complement the existing headline indicators. These additional indicators could come in the form of component indicators specifically addressing the gaps identified (for example, target 2: ‘enhancing ecological integrity and connectivity’), or additional straightforward binary indicators may suffice (for example, goal D: ‘adequate capacity-building is secured’). Additional component and complementary indicators could be developed by organizations currently focused on those specific aspects of the goals and targets (for example, human–wildlife conflict23) whereas additional binary indicators could be proposed by Parties and follow the methodology designed by the AHTEG.

General recommendations

Improving the coverage of the monitoring framework

The GBF’s monitoring framework has some important limitations. However, its adoption is a major step forward compared to previous strategic plans; the previous plan (the Aichi targets) did not have a monitoring framework, the use of indicators in national reports was optional and reporting was limited. Moving forward, the monitoring framework sets the stage for building and improving national monitoring systems and improving monitoring over time.

The limitations of the monitoring framework will be particularly important for countries to consider as they develop their national monitoring systems. Through the adoption of the mechanisms for planning, monitoring, reporting and review, Parties recognized that at the national level, each country should develop a national monitoring plan for monitoring their national biodiversity strategy and action plan and that this national policy should use headline, binary, component, complementary and national indicators as appropriate. Given the significant challenges in developing and implementing the indicators in the monitoring framework, it is highly unlikely that all Parties will use all of them. Because of capacity limitations, it is possible that some Parties will not report on all required binary and headline indicators. Additionally, the component and complementary indicators are optional, and the disaggregations of the headline indicators are recommended rather than mandatory, meaning these probably will not be applied by all Parties. Thus, gaps are inevitable and it is important for both Parties and the international community to see implementation of the monitoring framework as something that must be improved over time through both investments in national monitoring and scientific research. At this time, the biggest risk to effective tracking of global progress is a lack of ambition or capacity in implementing the monitoring framework.

Our results highlight that relying solely on the indicators required for national reporting will cover only some of the elements in the GBF. The monitoring framework could provide good coverage if the recommended disaggregations of the headline indicators, as well as the optional indicators, are implemented. For example, the current coverage for target 3 is entirely provided by disaggregations of headline indicator 3.1. A lack of ambition or resources from Parties could result in few component or complementary indicators or disaggregations being used and reported, especially for those Parties with more limited resources that must already be deployed on compiling the required indicators. In such a case, we would have little ability to judge whether most of the goals and targets were met in each country and at a global scale; much of the GBF would be unmonitored. Therefore, efforts must be made to ensure that recommended disaggregations and optional indicators are included in national monitoring plans and reported in the national reports.

Particular attention should be paid to all those elements assessed as ‘potentially’ covered. Work is needed to develop appropriate indicators for these 25 elements as their adopted headline indicators are not yet ready for national implementation (Fig. 2). This presents a short-term opportunity to improve coverage of the monitoring framework with more limited investment of time and resources and without the need for further negotiation. Rapidly completing the development and testing of these indicators would allow goal C and targets 6, 11, 13 and 21 to be monitored effectively.

Specific gaps can be addressed at the national level using national indicators that are not included in the current list and do not require negotiations. Parties may develop these indicators at the national level or international organizations may do so at the global level and then disaggregate to the national level. This approach would not systematically address the gaps in the monitoring framework but would improve coverage of the GBF for some Parties and make available additional indicators for consideration in the next rounds of negotiations. (It is expected that the list of component and complementary indicators will be updated at COP17 and potentially at future COPs24.) For example, while the monitoring of some aspects of freshwater resources and aquaculture are gaps, some Parties have chosen to report on their status using national indicators25,26.

It is unlikely that new headline or binary indicators will be adopted by Parties and added to the monitoring framework before the next strategic plan for the Convention is developed in 2030. However, further component and complementary indicators may be added if they meet the criteria for inclusion, but these will remain optional. Therefore, while there are opportunities to fill specific gaps with additional indicators, as discussed above, improving the monitoring framework should be seen as a long-term endeavour that will continue over several years. Understanding the underlying reasons for gaps provides an opportunity to improve global biodiversity monitoring efforts. In the following sections, we address the general requirements for an effective monitoring framework for today and into the future.

Data needs

Many gaps or issues of partial coverage are linked to data availability. There are historical reasons behind the incomplete coverage of biodiversity data globally27,28 that have resulted in poor coverage of many species, genetic diversity and ecosystem extent and integrity around the world, especially in tropical regions29. As such, improving sampling efforts of biodiversity data is a key priority for monitoring of the GBF, in particular for indicators A.1, A.4 and 2.1. Data collection, archiving and reporting efforts should follow the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable)30 and CARE (Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, Ethics)31 principles and take advantage of new technology on designing effective biodiversity monitoring systems to strategically fill gaps and compute indicators32,33,34,35. They should build on and make use of existing data infrastructures, tools and community-developed standards that provide mechanisms for sharing and integrating biodiversity data from diverse sources of evidence36.

Ideally, biodiversity monitoring systems should be designed to integrate in situ observations gathered by conventional research programmes, such as long-term ecological research networks37,38,39, or community-based monitoring and information and citizen science efforts40, with remote sensing data41 and expert judgement, to take advantage of big data42 and potential advances in artificial intelligence43. To monitor the goals and targets of the GBF and link biodiversity outcomes to drivers of change, these data will need to be linked to national census surveys and other relevant physical, economic and social measures. However, gaps exist in these datasets and national census surveys may need to be updated to reflect the needs of the GBF. For example, questions on mainstreaming (target 14) may help address a data-poor section of the monitoring framework. One important reason for this poor and declining44 biodiversity data coverage is the lack of investment and institutional support for biodiversity monitoring efforts45. However, many of the headline indicators are actively developed and supported by international organizations. If resourced, the same organizations can guide data collection, provide capacity-building and offer support to Parties. Additionally, civil society and volunteer efforts to collect biodiversity data provide significant value to states in administrative cost savings46 and should be promoted and integrated with government-led biodiversity monitoring systems.

It should be noted that there is a difference between asking Parties for more disaggregated data (which would increase the burden of reporting) and overlay of data provided by Parties with information from other sources (which implies more effort in analysing the collated data). Ultimately, the issue of data collection, whether done by Parties or in collaboration with non-governmental organizations, is one of capacity47. Resourcing additional data collection efforts will be a significant challenge for many Parties and will require North–South, South–South and triangular collaboration, as well as financial resources to be made available.

Methodological needs

The issue of data is linked to the tools and methods currently available to detect trends in biodiversity and benefits derived48. Adapting the way biodiversity change is understood to better reflect the data available today is necessary to avoid difficulties in measuring change49. Furthermore, the scientific community has not yet come to a consensus on understanding and monitoring different facets of biodiversity and people’s needs50,51. Indeed, the needs of the GBF go beyond biodiversity data and require that information on drivers of biodiversity change and societal outcomes be monitored (for example, for targets 9, 11 and 12), potentially requiring cross-sectoral data sharing agreements. In some cases, this results in the need for entirely new data collection and analytical methods, such as for financial flows52 (indicators D.1, D.2 and D.3) and access and benefit sharing53 (indicators C.1 and C.2). Specifically for access and benefit-sharing indicators, legal frameworks (for example, the Nagoya Protocol54) did not foresee the need to measure societal outcomes but rather national compliance metrics. Additionally, social processes related to participation, equity and rights (for example, for targets 22 and 23) also need effective monitoring to ensure that all parts of the GBF are implemented effectively.

Integrating across data sources and between social and ecological data is a significant challenge that requires well-designed pipelines and data products that can standardize information and make it usable for indicator calculation. For example, essential variables for biodiversity55,56 and ecosystem services57 can standardize multiple data types, enabling the use of analytical pipelines to compile indicators and support further development efforts. Additionally, approaches to recognize and support the role of Indigenous and local knowledge as complementary to the conventional scientific processes are improving58,59 but more remains to be done for these to be systematically applied and fully inclusive60.

One of the strengths of the monitoring framework is that it will enable consistent reporting of indicators by countries, supporting comparisons across countries and aggregation for regional and global synthesis. For example, the AHTEG recommended a consistent approach to compiling and reporting indicators related to ecosystems, their protection, restoration, sustainable use and status. This would allow the impacts of the actions (for example, restoration indicator 2.1) to be tracked on outcomes, such as the extent of natural ecosystems (indicator A.2) and their risk status (indicators A.1 Red List of Ecosystems). The AHTEG recommended using the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Global Ecosystem Typology (GET)61, endorsed in March 2024 as an international statistical classification by the UN Statistical Commission62, to support consistent reporting and disaggregation of ecosystem-related indicators by ecosystem functional group (level three in the typology). To do so, countries would cross-reference their national ecosystem classifications and maps with IUCN GET to enable reporting based on national ecosystem data and assessments. Significant progress has been made by Parties to map ecosystems63 and tools are available to facilitate advancement64. Accelerating adoption would potentially allow a complete picture of given ecosystem groups (for example, coral reefs or tropical lowland rainforests) within a country, globally and across indicators.

An important focus area for systematic indicator calculation is interoperability65,66. Designing analytical pipelines capable of fully integrating and interpreting data types and meaning67,68 and producing indicator calculations will significantly reduce the capacity needs of Parties69. Prioritizing these efforts to compile headline indicators and share code openly with all Parties could significantly reduce the equity and capacity barriers to monitoring the GBF and free up resources for Parties to include additional optional indicators relevant to their needs. Some of the infrastructure to enable this process is already in place70,71,72 but additional efforts are required to fully operationalize it.

Finally, accounting for and reporting on uncertainty in biodiversity estimates and indicators will be essential to effectively guide the decision-making and implementation of the GBF. Uncertainty in trend detection capabilities has shed doubt on understanding global biodiversity change73 and on the ability to detect improvement or further decline in biodiversity49. One solution is to use modelling techniques, such as Bayesian inference49, that can allow updated estimates of progress as new data and evidence arise within a robust and rigorous framework for dealing with uncertainty49,74. Communicating uncertainty in indicator values to decision and policymakers is crucial for the monitoring framework to go beyond progress tracking and effectively support implementation.

Building the infrastructure to monitor biodiversity globally

The GBF is a common endeavour that, although Party-led, requires nations and stakeholders in them to work together75. The upcoming fast-track assessment by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services on monitoring biodiversity and nature’s contributions to people (NCP) will assess current capacity, identify needs and suggest solutions76. One solution is to support international cooperation by establishing a global biodiversity observing system (GBiOS). A GBiOS would support the implementation of national biodiversity monitoring networks32,35,77,78 while assembling an international system similar to that used to monitor trends in climate (the World Meteorological Organization Integrated Global Observing System). This system allows countries to opt in and thus benefit from funding and shared resources and technologies, such as data and modelling infrastructure79. Therefore, by following this model, GBiOS could exist as a federated international network of national monitoring systems66,78. Over time, GBiOS could allow multilevel assessments of biodiversity trends that contribute to calculating indicators.

Headline indicator 21.1, on biodiversity information for monitoring the GBF, is currently under development (Fig. 2). At the highest level, this indicator could be evaluated if countries reported the number of headline indicators where national datasets, models, monitoring schemes and information tools are available and used. If aggregated and calculated over time, this would capture within and across country-level trends in the access and use of data on biodiversity outcomes. Development of Indicator 21.1 along three dimensions would measure the coverage in space and time of used and accessible data capturing trends in different biodiversity dimensions, the recognition and use of Indigenous and local knowledge of biodiversity, and the quantity and scope of active biodiversity monitoring activities and the data they produce.

This effort could be supported in the long term by information made available by GBiOS, by filling gaps in data coverage that hinder calculation of headline 21.1. Other indicators (for example, A.2, B.1, 2.1, 3.1) could rely on data collected and shared through GBiOS, addressing gaps in geographical coverage and data availability. Making GBiOS a reality requires (1) a sustainable and inclusive governance model allowing countries to opt in and actively participate; (2) a funding mechanism to support Parties looking to invest in their national biodiversity observation networks; and (3) the human capacity and technical infrastructure required to connect countries to an operational international network21. When brought together with other knowledge types, including Indigenous and traditional knowledge, scientific expert judgement, socio-economic data and information on governance and regulation, a GBiOS could generate the information needed to guide investments in monitoring capacity to fill the gaps in the monitoring framework.

Such a system would promote synergies between the CBD and the global climate agenda80. Climate monitoring systems are more advanced than those of biodiversity yet both crises are closely linked81,82. Some important differences between climate and biodiversity have limited efforts to connect these Conventions and their data collection systems: biodiversity metrics are less standardized55; their scale of change is more local and sensitive to small-scale changes83; methods for data collection are more diverse34; and the global policy relevance of the biodiversity crisis has lagged behind that of the climate crisis84,85. Yet, there are many synergies between monitoring climate and biodiversity (for example, nature-based solutions are an important component of climate policy86,87); connecting them would improve understanding of biodiversity change and support efficient data collection efforts78. Taking advantage of the capacity and knowledge already built in the climate space may also further the implementation of national and global biodiversity observing systems. Other sectors, such as those carrying out environmental impact assessments, also produce important knowledge and could contribute to monitoring of outcomes under the GBF88.

Cross-cutting considerations

Section C of the GBF outlines the cross-cutting considerations for the GBF. It requires that the implementation of the GBF be consistent with the rights and contributions of IPLCs, different value systems, human rights, gender, intergenerational equity and human health7. While no indicators were specifically designed nor included to measure progress towards Section C, its considerations are partly addressed by using the existing headline and binary indicators as informative proxies. Indeed, some indicators are particularly relevant (for example, 9.1, 14.b, 22.b and 23.b), while others invite additional data collection to allow relevant disaggregation (for example, for IPLCs, women and youth for A.1, B.1, C.1 and C.2).

The considerations can be partly addressed by using indicators and disaggregations relevant for the defined social groups in Section C. Specifically for IPLCs, the CBD’s four traditional knowledge indicators89 could be used to complement the headline and binary indicators. In the monitoring framework, these are component or complementary indicators for certain targets and can provide a basis for disaggregating existing headline indicators (for example, for indicator 3.1 by disaggregating according to Indigenous and traditional territories). Further, the human rights-based approach to monitoring90,91 is already applied to the traditional knowledge indicators and could be extended to the whole monitoring framework. Finally, particular attention is needed to address disaggregation according to gender, age, disability, IPLCs, education and socio-economic status. Although data availability and methodological challenges may limit the use of disaggregated data in the next national reports, the gaps, priorities and opportunities for data disaggregation and participatory approaches should be identified and advanced to improve future monitoring.

The monitoring framework further invites Parties and relevant organizations to support community-based monitoring and information systems (CBMIS). The contribution of CBMIS to monitoring progress and achieving biodiversity targets is well documented92. Some community-based monitoring tools implementing a human rights-based approach, such as the Indigenous Navigator93, are already operational. CBMIS provide cross-cutting data and knowledge useful for monitoring multiple targets and Section C94. Specifically, CBMIS collect data in remote areas where gaps are common even for well-developed indicators, as well as providing traditional knowledge relevant to the GBF59,95. Furthermore, CBMIS are community-focused, reflecting the needs and priorities of their members and different value systems96. Typically, CBMIS also collect information on health and human rights outcomes. Finally, community-based monitoring efforts in collaboration with scientists have been a cost-effective way of furthering understanding and managing biodiversity97,98. As such, these monitoring systems should be an integral part of data collection efforts wherever they exist.

Nevertheless, there is a need for more work to be done across all the cross-cutting elements of Section C because gaps remain in our understanding of how these topics interact with biodiversity. This was not assessed in detail in the gap analysis and remains an open area for research. This work is essential given that Parties often noted difficulties in taking Section C into account in the development of their national targets; only around one-third of the national targets submitted by Parties by October 2024 contained information on how the issues identified in Section C were being taken into account99.

Next steps in implementing the monitoring framework

Reviewing and updating the monitoring framework

The work of the AHTEG, in collaboration with many organizations and individuals, has significantly improved the readiness level of existing indicators and the ability of Parties to use the monitoring framework8. Work on improving those indicators currently in the monitoring framework should be encouraged and appropriate organizations resourced. After the next round of reporting, there will be an opportunity at COP17 to review how the monitoring framework has been operationalized by reviewing what was reported by Parties. This engagement is key to the success of the monitoring framework.

The monitoring framework is expected to be kept under review thereafter, providing an opportunity for updates and improvements, based on its implementation by Parties, from COP17 onwards. This review process is expected to provide space for the addition of new, relevant and operational optional indicators as well as the updating and improvement of existing indicator methodologies. A formal process of update and review for the monitoring framework, akin to the annual refinement and quinquennial comprehensive review of the SDG indicators14, but focusing on updating the list of indicators as well as their methodology, could be established to fill gaps and improve the monitoring framework. Such a process could learn from the AHTEG and include experts and stakeholders representative of the GBF with a clear mandate and resources to update the monitoring framework.

Addressing resourcing and capacity-building priorities

The most likely barrier to a successful implementation of the monitoring framework is one of human and financial capacity. Issues of equity are particularly relevant in this context because areas with the most biodiversity are often those with the least capacity to monitor its status100. Without the resources to implement the required indicators in the monitoring framework, many Parties will not be able to report on them and gaps will remain unfilled; thus, uncertainties about progress under the GBF will persist. Through COP decisions, Parties have committed to prioritizing biodiversity planning and monitoring nationally. Financial resources are now needed to establish and strengthen national and regional monitoring frameworks. These resources should be used to build nationally relevant biodiversity observation systems with the people, technologies and knowledge systems needed to implement the monitoring framework.

The challenge in funding monitoring will be particularly acute for those Parties with the least resources, for which multilateral and innovative funding sources may be required. While governments will need to invest more into monitoring, private sector actors also have a role in enhancing funding levels and deploying innovative solutions. Around half of the world’s gross domestic product is moderately to highly dependent on biodiversity101, meaning that private companies and financial institutions have a considerable stake in this issue. Direct engagement of the private sector in supporting biodiversity monitoring efforts102 must respect the rights of all communities involved and ensure that all data are collected fairly and equitably. Additionally, the implementation of benefit-sharing agreements under the CBD and its Nagoya Protocol, as well as the newly created multilateral mechanism for the fair and equitable sharing of benefits from the use of digital sequence information on genetic resources103, may help build capacity among those Parties where the genetic resources are being sourced104, as well as among IPLCs.

Finally, beyond national efforts, global cooperation is required to resource the organizations that are supporting methodological research and capacity-building around the indicators. This is essential for the full development of indicators and their disaggregation, to enhance harmonization among indicator frameworks when relevant (for example, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change work on indicators under the global goal on adaptation) and to increase the coverage of indicators that support the effective implementation of the monitoring framework over the long term.

Conclusion

The adoption of the monitoring framework was a monumental achievement. This decision by Parties represents a shift in how transparency and responsibility will be assured. The Convention has moved away from national reports containing largely qualitative narrative, to reports requiring quantitative indicators. Despite its existing limitations, the monitoring framework marks a paradigm shift in implementing the CBD. Further developing and implementing it will be challenging, but changing the status quo is never easy.

The monitoring framework has been developed considerably since its first draft was negotiated7. The present analysis shows that, despite the gaps identified, there is a large quantity of data, indicators and knowledge available to implement the monitoring framework, making use of the guidance and resources available. It now stands ready to inform on progress towards achieving global goals and targets in a way that has not been previously possible. However, its effectiveness will depend on the degree to which Parties implement it. While all Parties must balance multiple priorities and face practical, technical, financial and social constraints on what can realistically be monitored, the ambition of Parties in implementing monitoring and reporting indicators will determine our ability to judge progress towards the goals and targets, and, ultimately, whether they have been achieved. The monitoring framework provides an opportunity to develop and invest in national biodiversity monitoring systems and to improve national and global data sharing and connection of monitoring systems.

The academic and non-governmental organization communities have roles to play in supporting implementation by providing capacity-building, training and data-informed workflows, which are required to lower the barriers to implementation, especially for developing nations. Academic and citizen scientists, non-governmental organizations and IPLCs have an important role to play in collecting data and compiling indicators to help Parties report on the many indicators of the monitoring framework. While the gaps identified in this study are concerning and should be addressed, a failure to implement the monitoring framework will result in a much greater number of gaps. We strongly encourage the scientific community and other relevant actors to engage with and support Parties in their efforts to implement the monitoring framework. Its implementation through the seventh national reports expected in 2026 will provide a first opportunity to gauge the adequacy of monitoring and the extent of progress towards achievement of the GBF.

The monitoring framework will be essential to delivering on the ambition of the GBF by 2050. It should be considered a global learning mechanism, allowing enough flexibility for Parties to meet their objectives while sharing progress and experiences globally to improve outcomes for the whole of society. The achievement of the GBF targets for 2030 and the vision and goals for 2050 depend not only on the comprehensive and effective implementation of policies and actions but also on effective implementation of the monitoring framework.