A new immigrant detention center, dubbed “Alligator Alcatraz,” at the Dade-Collier Training and Transition Airport, located within the ecologically sensitive Big Cypress region of the Florida Everglades, has moved forward without required environmental reviews or public input. Development of the large facility could have devastating consequences for threatened and endangered species.

The detention center, which Florida Attorney General James Uthmeier proposed in June, sits on federally protected land critical for several endangered species, including the Florida panther (Puma concolor coryi), eastern indigo snake (Drymarchon couperi) and Florida bonneted bat (Eumops floridanus). The latter, found only in South Florida, is one of the most critically endangered mammals in North America, and the site includes critical habitat required for roosting and foraging. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has listed Florida panthers as endangered since 1967. They suffer from habitat destruction along with increased vehicle mortality driven by associated roads and traffic contributing to their decline. The species has an estimated population size of 120–230 adults. The project site sits within the Primary Zone of the Panther Focus Area used by breeding pairs of panthers. Four panther dens exist within 12 kilometers of the site.

Several people and organizations oppose the project. Friends of the Everglades and the Center for Biological Diversity issued a 60-day notice of intent to sue on June 27 over the failure to consider environmental impacts of the project, including legally required reporting on the effect on species under the National Environmental Policy Act.

Enlarge

A map of the Big Cypress Swamp Jetport site taken from the original environmental impact report. Credit: U.S. Department of the Interior

The groups challenged the project’s legality and ecological impact with a Notice of Violations of Federal Environmental Law issued on July 11 and a notice of violating the ESA. The notice detailed changes and problems already occurring at the facility and issued a legal warning for federal and state authorities to stop development and operation. So far, more than 40,000 people have voiced their opposition to the facility, according to sources at the Friends of the Everglades.

Progress or peril?

Before it became the site of an immigration detention center, the Dade-Collier Training and Transition Airport—nicknamed TNT—was an ecological conflict flashpoint for one of the most defining environmental fights in U.S. history.

The Big Cypress site lies at the headwaters of the Everglades, where slow-moving overland flow feeds ecosystems all the way to Florida Bay. In the late 1960s, the federal government proposed building the Miami Jetport in the Big Cypress Swamp. The Dade County Port Authority purchased 39 square miles and planned to build a jetport five times the size of JFK International Airport. Its purpose was to serve the era’s supersonic jets as the largest planned airport in the world at the time, a symbol of “progress” during that period.

Construction of the jetport began in 1968. Meanwhile, environmental advocates worried the jetport would have destroyed the Everglades’ hydrologic heartbeat. Joe Browder, the southeastern representative of the National Audubon Society, joined forces with 79-year-old Marjory Stoneman Douglas, who founded the nonprofit Friends of the Everglades in 1969, to lead a grassroots fight against the jetport.

Douglas mobilized a grassroots campaign that changed the course of environmental history. The campaign against the jetport showed the world that swamps had a voice and a fierce defender. Together, they worked to prevent the destruction of this ecologically sensitive area.

The “Environmental Impact of the Big Cypress Swamp Jetport,” unofficially known as the “Leopold Report,” was the first ecological impact report in Florida, authored by hydrologist Luna Leopold of the United States Geological Service for the Department of the Interior. When the report was officially released in 1969, it stated that the jetport would “inexorably destroy the South Florida ecosystem.” This document laid the groundwork for current National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) regulations.

“One cannot drain a swamp and save it at the same time.”

The Leopold Report

Nathaniel Reed, who served as then Florida Governor Claude Kirk’s senior advisor, used the Leopold Report to persuade the governor, who had initially supported the jetport plan, to reverse his opinion and oppose the project. In 1970, President Nixon cut funding. Only one runway had been completed, and today’s TNT saw minimal use before the detention center was built. The victory helped catalyze the modern environmental movement with the passage of NEPA, the Clean Water Act (CWA) and the strengthening of the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

“The fabric of environmental laws was being stitched together because of these threats, including the jetport,” said Eve Samples, the current executive director of the Friends of the Everglades. Samples keeps a framed photograph of the runway in her office as an emblem of “what we fight for in Florida and how victories can be imperfect,” she said.

A new front in an old war

In 1974, Congress established the Big Cypress National Preserve to protect over 500,000 acres in South Florida, including the area of the proposed jetport. The federal government recognized the Miccosukee, Seminole and Traditional people’s permanent rights to occupy and use the land in traditional ways. They also gained first rights to develop income-producing businesses related to the resources and use of the preserve.

Now, the TNT site in Big Cypress finds itself back in the heart of the battle as history threatens to repeat itself. “We find ourselves coming full circle here,” said Marisa Carrozzo of the National Parks Conservation Association, one of the original organizations that was part of the coalition against the original jetport site and is opposed to its use as a detention center facility today.

The “Alligator Alcatraz” detention facility sits on the same runway that Marjory Stoneman Douglas and the diverse coalition of groups, individuals and Tribes had fought to prevent from expanding.

“Even though this isn’t a massive international airport, the concerns still exist.” Samples said.

Alligator Alcatraz was fast-tracked for construction at TNT without the environmental reviews required by law. Conservation groups argue that federal and state agencies, including the Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the Federal Emergency Management Agency and Florida’s Division of Emergency Management, have sidestepped essential legal requirements under the ESA, CWA and NEPA. Specifically, the agencies failed to initiate ESA Section 7 consultation, a mandatory process to ensure federal actions do not jeopardize listed species or degrade their critical habitat. They also did not secure permits under the CWA.

“It’s really like the government has gone rogue,” Samples said.

The first signs of changes in the Everglades

Scientists have found that “Alligator Alcatraz” is already harming the Everglades. This is a remote, highly sensitive ecosystem, so the early construction activity is disrupting wildlife and damaging the environment.

Enlarge

A juvenile Florida bonneted bat. Credit: Enwebb

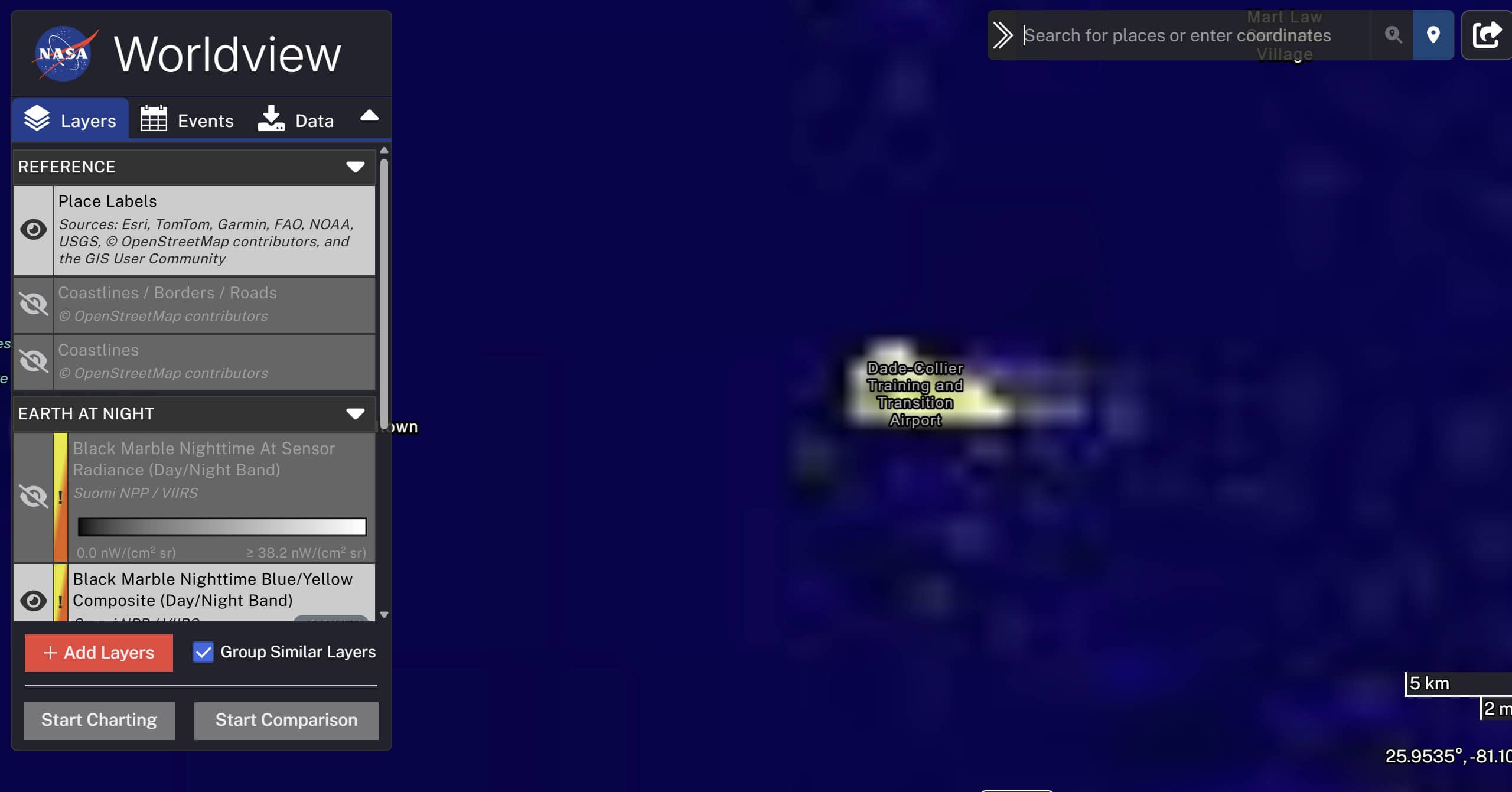

Big Cypress National Preserve, one of the darkest remaining areas east of the Mississippi River and an officially designated International Dark Sky Park, now faces visible degradation of its night skies. Industrial, stadium-style lights are left on 24/7, and light pollution from the developing detention facility can be seen more than 15 miles away. “We are deeply concerned about light pollution,” said Marisa Carrozzo, with the National Parks Conservation Association. Light pollution is an ecological stressor that has the potential to disrupt nocturnal species, such as the Florida panther and Florida bonneted bat, undermining the National Park Service’s mandate to protect natural night conditions.

The surrounding landscape is also being physically transformed. Aerial imagery shows fresh expansions to the paved footprint of the site using asphalt, including areas historically classified as wetlands. These wetlands appear to the plaintiffs as hydrologically connected to navigable waters within Big Cypress, raising concerns under the CWA. Additionally, builders installed approximately 28,000 feet of barbed wire fencing, which fragments habitats and acts as barriers to wildlife movement, effectively displacing species that rely on contiguous habitat. What’s more, fuel combustion from generators and vehicles produces air pollutants, and potential spills risk contaminating wetlands and groundwater. Increased road traffic around the facility also raises the likelihood of roadkill of endangered and threatened species. Deportation flights would increase air traffic and increase the potential for wildlife interactions. Light, sound, human activity and physical barriers, like fences and barbed wire, are expected to evict wildlife from the area around the TNT Site.

The Florida bonneted bat requires stable foraging grounds. Yet according to the Notice of Violations of Federal Environmental Law, members of the public have taken photos of vehicles from a pest control company entering and exiting the TNT Site. The concern of the plaintiffs is that the use of pesticides in such a sensitive ecosystem threatens poisoning insects, reducing available prey and potentially contaminating water resources. These effects could trigger cascading effects on bats, birds and aquatic life.

The plaintiffs expressed that by failing to complete consultation before embarking on the project, the federal and state agencies, organizations, businesses and/or individuals engaging in these activities have failed to ensure they will not jeopardize the continued existence of species or adversely modify critical habitat. Therefore, they are violating the ESA.

“We might not see [all impacts] instantaneously, but things that happen instantaneously are probably some of the worst effects that can happen,” said Lucas Osceola, assistant chairman of the Miccosukee Business Council.

Enlarge

A picture of the view from Tamiami Trail, approximately 15 miles from the TNT site on July 7, 2025 included in the Notice of Violations of Endangered Species Act. Credit: Betty Osceola

Miccosukee Tribal leaders—the land stewards immemorial—have also raised significant concerns. Osceola spoke out about the potential long-term effects on the environment, as well as the health and safety of Indigenous communities and the disruption of generational knowledge-sharing and cultural practices.

“We want to make sure that we defend the Everglades and all of our creatures within it, as well as all of South Floridians,” Osceola said. He also emphasized the stark contrast between the Tribe’s slow, deliberate approach to development, including five- to 10-year environmental studies, and the rapid and unreviewed development at the TNT Site. “We’re talking about more than doubling the population of the Florida Everglades,” he said. “I just wish that people would follow environmental study timelines.”

Osceola also voiced concerns about storm vulnerability, drawing from experience with Hurricane Andrew, when debris was scattered throughout the Everglades. Temporary structures at the TNT site may not withstand extreme weather, risk people’s lives and increase the risk of long-term environmental damage and contamination.

Federal and state agencies did not provide a comment regarding the environmental impact of the project upon publication of this article. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission did affirm that they are “proud to be a partner in this important mission to ensure the safety of the facility, protect surrounding natural resources and maintain public safety throughout the area.”

‘It’s not too late’

As the Everglades faces yet another critical turning point and the fabric of environmental policy is stretched thin, the voices of those who have long protected this landscape urge the public not to stay silent.

“Just because you clean up doesn’t mean you can make a mess again,” Osceola said, calling for accountability and long-term thinking. He reminds us that protecting the Everglades is not just about policy; it’s about people, tradition and future generations. “Reach out to all your local, county and state representatives to make sure that you let them know that the Everglades is for everyone, and we want to protect it for generations to come,” Osceola said.

While the threats are serious, advocates remain hopeful. “It’s not too late. Think about how much more we can lose. We can still reverse course,” Samples said. But time is short, Douglas said. “Conservation is now a dead word … You can’t conserve what you haven’t got.”